Scaling Scrum to the limit

You’re likely to have been asked the question: “we need to go faster, how many more people do we need?” Most people naturally understand that just adding a random number of people isn’t likely to make us any faster in the short run. So how do you scale Scrum to the limit? And what are those limits?

You’re likely to have been asked the question: “we need to go faster, how many more people do we need?” Most people naturally understand that just adding a random number of people isn’t likely to make us any faster in the short run. So how do you scale Scrum to the limit? And what are those limits?

Meet Peter, he’s a product owner of a new team starting on the greatest invention since sliced bread. It’s going to be huge. It’s going to be the best. Peter has started on this new product with a small team, six of his best friends and it has really taken off. In order to meet demands while adding new features, Peter needs to either get more value out of his teams and if that is no longer possible, add more team members.

He and his teams have worked a number of sprints to get better at Scrum, implemented Continuous Integration even to deliver to production multiple times per day. It is amazing what you can do with a dedicated team willing to improve. But since their product was featured in the Google Play Store they’ve found themselves stretched to their limits. Peter has found himself in the classical situation in which many product owners and project managers find themselves. How do you replicate the capabilities of your existing team without destroying current high-performance teams? He contacts a good friend, Anna, who has dealt with this situation before and asks for her advice.

Anna explains that there are two options of gradual growth that have a very high chance of succeeding with limited risk to his productive team.

1. Grow and split model

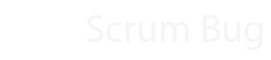

In this model, new team members are added to the existing team, one team member at a time and taking enough time to let the new member settle before adding the next. Once the team reaches a critical point, a natural split is bound to happen and you’ll end up with two or more smaller teams. Peter remains the sole Product Owner (a product is always owned by a single owner in Scrum), but as they grow they may add an additional scrum master to help facilitate and help the teams to keep improving.

Most often the split happens naturally when a team grows beyond a certain size. This allows the team to self-manage their new composition. However, the new teams may never perform as well as the original team.

2. The apprentice model

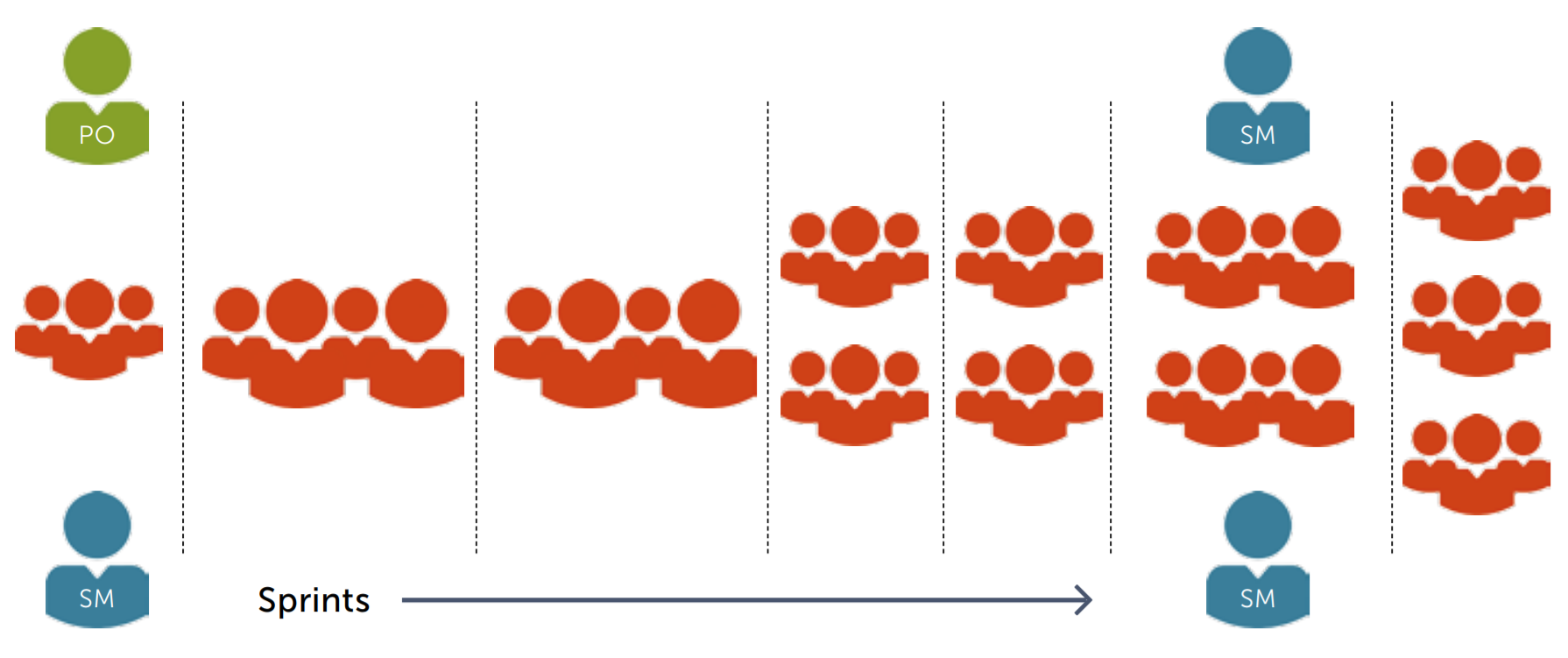

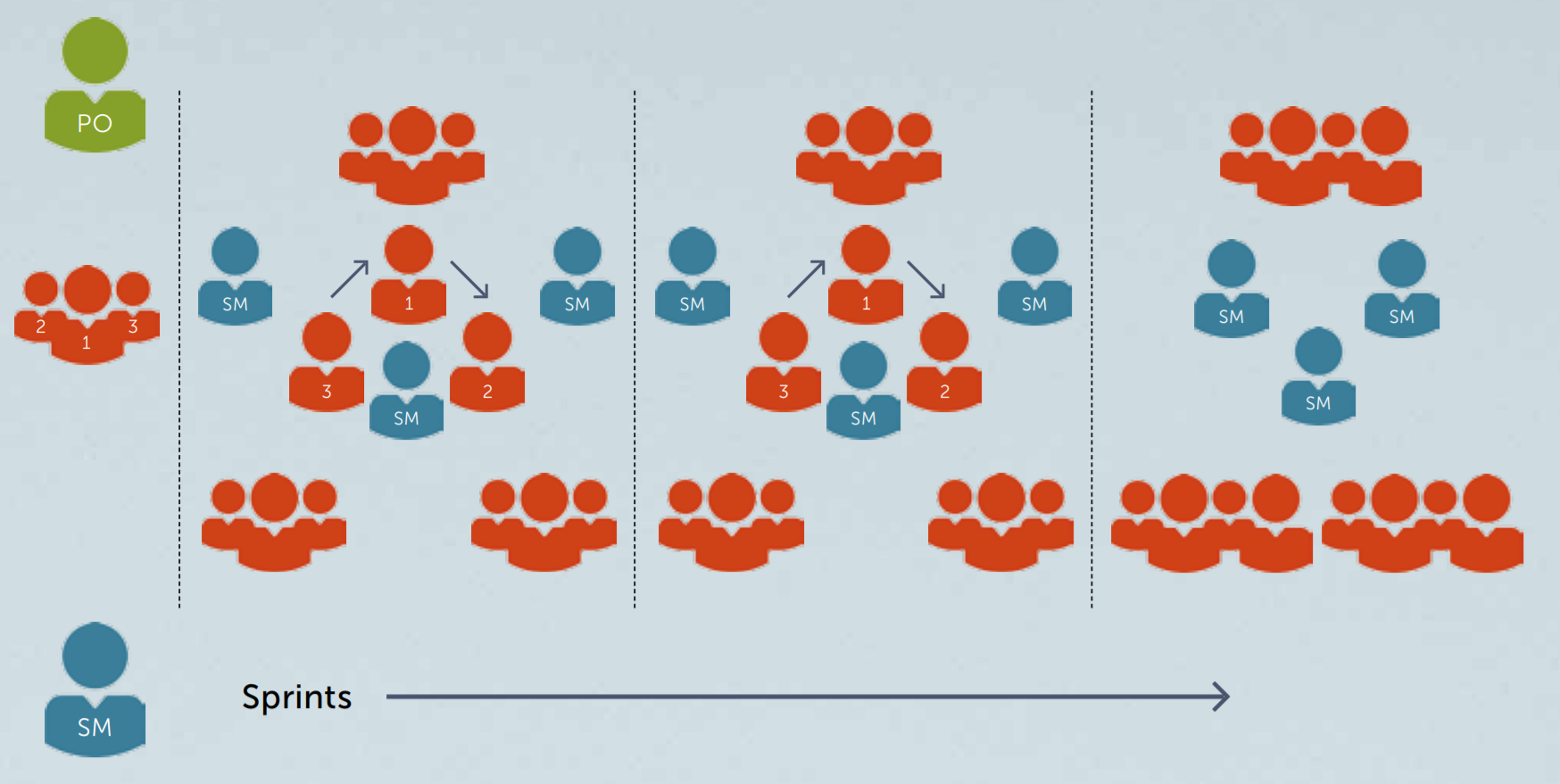

The second model, Anna explains, uses an age-old model to train new people on the job. In the apprentice model the existing team takes on two apprentices who are trained in the ways of working and the functional domain. After a couple of sprints these apprentices reach their journeyman status and start a team of their own.

The biggest advantage of this model is that the original team stays together. They do have to onboard and teach the apprentices, which is likely to impact the way they work together, but this model has a much higher chance of retaining the productivity of the original team.

It may take a few sprints for the new team to reach the same level of productivity as the original team had, but you’ll have a higher chance of keeping your first team stable and productive. Unfortunately, in this model there are no guarantees either. Adding new people to an existing team can have lasting effects, even after these people leave.

These effects can be both positive and negative. E.g. they may bring along a new testing technique that helps everyone become more productive, or they may involve new insights that cause division among the original team. Depending on the team, they may be able to benefit from both, but it may also tear them apart.

It’s always the case that the original team will now have to learn to cooperate with the newly formed team, which will likely have a massive impact on their productivity.

Knowing when to stop scaling

Peter asks his team which model they feel most comfortable with and the team decides to start with the grow-and-split model, and after they’ve split off into two teams, adopt the apprentice model to grow further if needed.

He also asks Anna to join his company. She takes up the mantle of Scrum Master and focuses on helping the teams improve and helps them discover solutions for many of the problems introduced by working with multiple teams.

Meanwhile, Peter keeps asking the teams to train new team members and steadily the number of teams grows.

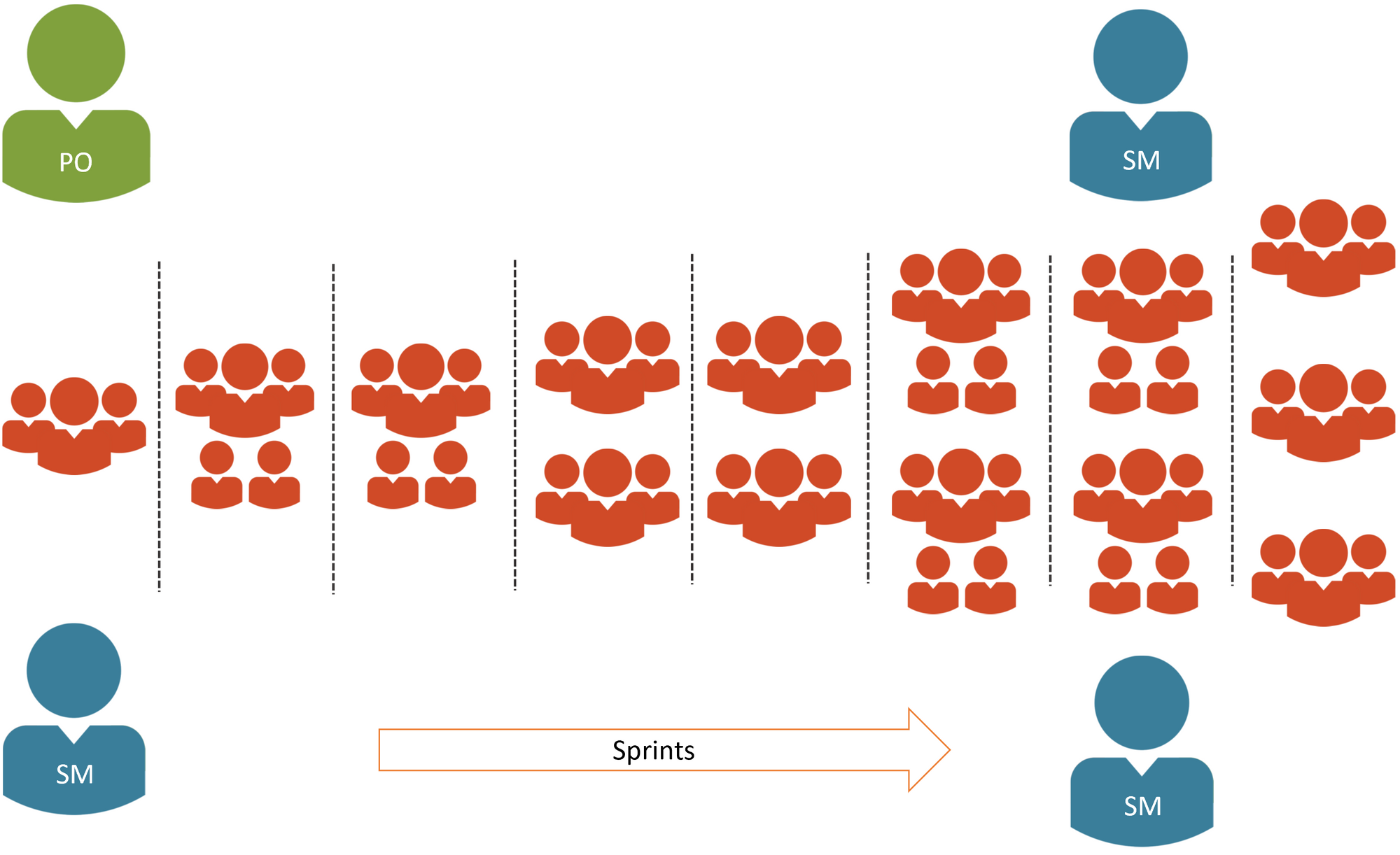

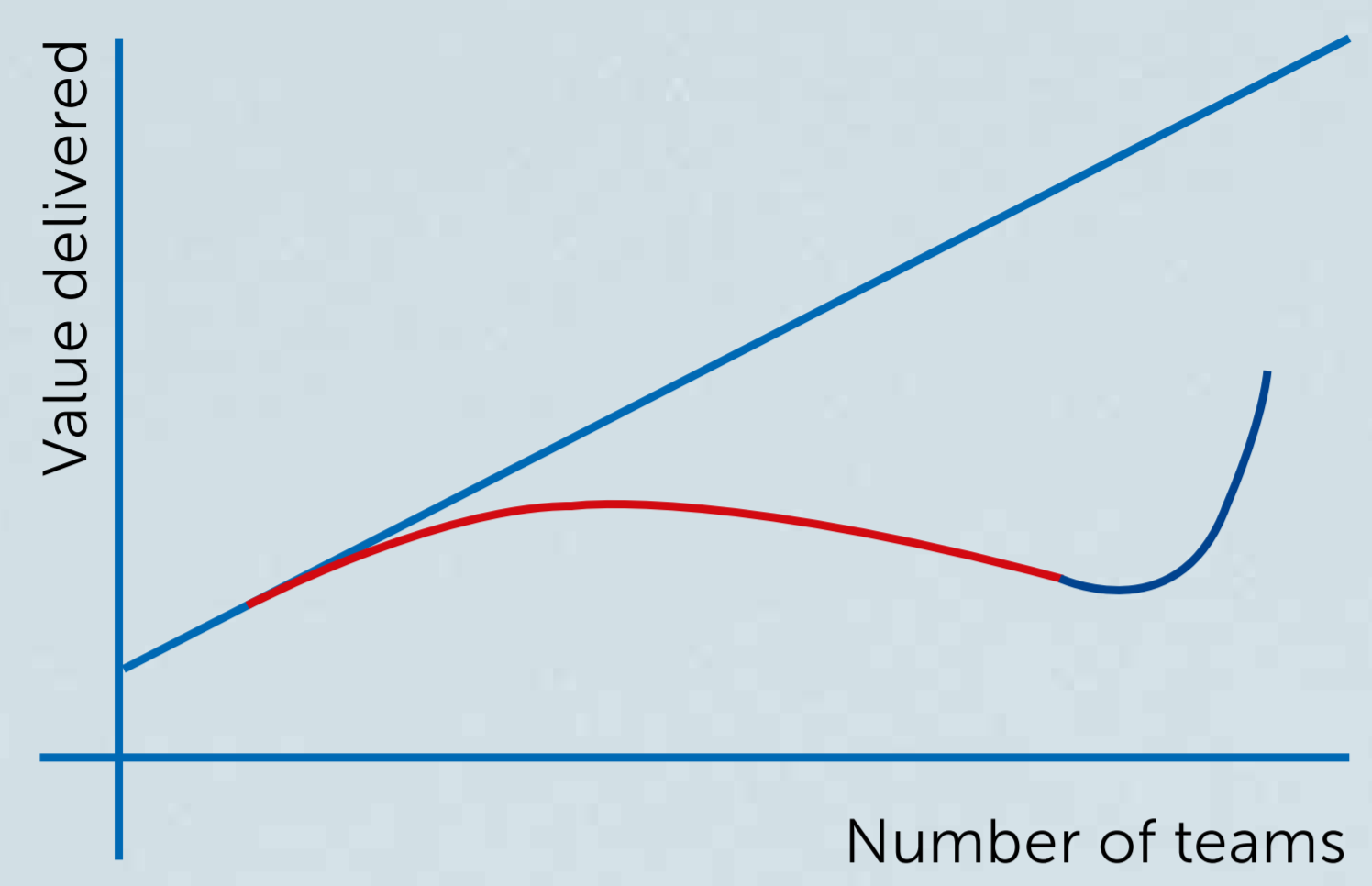

One afternoon Anna comes knocking on Peter’s door and shows him a couple of statistics she has kept for as long as she has been working in the company. According to her statistics, she had been tracking the value delivered per sprint as well as each team’s velocity - the latest additions haven’t been able to really deliver more. She argues that the overhead of working together with so many teams has reached the maximum sustainable by the current architecture. She asked the teams and found out that people are tripping over each other’s work, integration regularly fails, and people are spending too much time in meetings and not enough time on “real work”. Despite the practices she has introduced, such as cross team refinement and visualization of dependencies, it seems that they have reached the maximum size for the product.

While Peter is a bit disappointed, he has to admit that Anna warned him that he couldn’t just keep adding people and expect an ever-increasing amount of work to be delivered.

Useful metrics while scaling

While velocity (story points delivered), hours spent and number of tests passed are all viable ways of tracking progress for a development team, it’s easy to measure the speed at which worthless junk is being delivered to production.

This is why Anna also kept track of other metrics, such as value delivered, customer satisfaction (through app store reviews), incidents in production (through the monitoring tools they have in place) and more.[1]

Keeping statistics about the amount of value delivered while you’re scaling is important. You will probably find that while the total number of teams increases, each new team adds less and less value. This is a sort of glass ceiling that you may hit sooner or later. Breaking through it may require drastic changes to the application’s architecture or to the way the teams work together.

As Peter and the original team never expected the product to take off this fast, the architecture of the application was put together a bit haphazardly. And under the pressure to deliver, they cut a few corners left and right. He calls all of his teams into the company canteen and explains his predicament. Each team selects one or two of their most experienced team members and they form a temporary team of experts to figure out how to break up their little architectural monster. After peeling off a few functional areas and refactoring them into smaller, individually deployable parts of a cohesive functional unit, it quickly becomes apparent that this new architecture prevents them from tripping over each other’s toes.

You may have heard of this model before: small functional cohesive units of code that maintain their own data and that are called Microservices. These small units are ideal to form teams around and give these teams a lot of freedom.

Could we have done it differently?

Sometime later Peter finds Anna in the company coffee corner and asks her whether they could have taken another approach, one that would have shown the issues in their original architecture at an earlier stage of their product’s development. He also wonders whether they could have scaled faster by hiring experienced teams.

Anna explains that there was a third option she never explained to Peter, because it carried a much higher risk, and she didn’t dare risking the product. The third option was to quickly add a number of teams all at once, preferably teams of people who had already had some experience working together and that had experience working at such scale. At the same time, the original team members would be scattered among the newly formed teams, optionally rotating to share their specific knowledge of the domain or processes, and to explain the architecture and infrastructure In this model, given that you hit the problems in the established processes and in the architecture head-on, everyone needs to work together to quickly find solutions to all of the problems they encounter. If they manage this, they may be able to quickly find a way to work together. They may, however, also completely come to a stand-still or the amount of conflict may reach levels unimagined before.

3. Scatter and rotate model

To ensure the new teams have equal access to the knowledge and skills of the original team, the original team members often rotate among the newly formed teams or they are not dedicated to any team for a few sprints, before everything settles down.

If this model had succeeded, they may have been able to scale much faster. However, they could also have been out of business.

Peter reflects that had they had a direct competitor in the market who was able to deliver much faster, they could have taken this risk. But it would have been an all-in gamble. He's glad they weren’t in that situation.

Conclusion

There isn’t really a hard limit in terms of how many people can contribute to an agile product or organization. But clearly there are limits to the pace at which you can grow, to the amount of control you can have over what is going on in every team, and to what the product’s or organization’s architecture and processes can sustain.

There are multiple models to grow your ability to deliver value. While adding teams may seem the easiest solution, investing in continuous integration, automated deployments, and a flexible architecture may deliver more sustainable value faster.

When you do need to scale beyond what’s possible with a single team, remember that if you’re not ready for it, you’ll exponentially scale your team’s dysfunctions.

To be very blunt, if you scale shit, you end up with heaps of it. When you’re able to deliver quickly, efficiently and professionally, you can scale your teams. Keep measuring while you scale and keep evaluating your way of working, collaboration and architecture. Using your statistics, you can make an informed decision whether to scale further. Without them, you may be degrading your ability to deliver value without ever knowing it. Keep inspecting your processes, tools, architecture and team composition regularly. Your team will probably know what to improve in order to deliver more of the right things more efficiently.

Would you like to know more? Join a Scaled Professional Scrum class to experience Scrum with Nexus hands-on.